The Annual Pattern of Life – Buffalo Niagara Focus

Preface

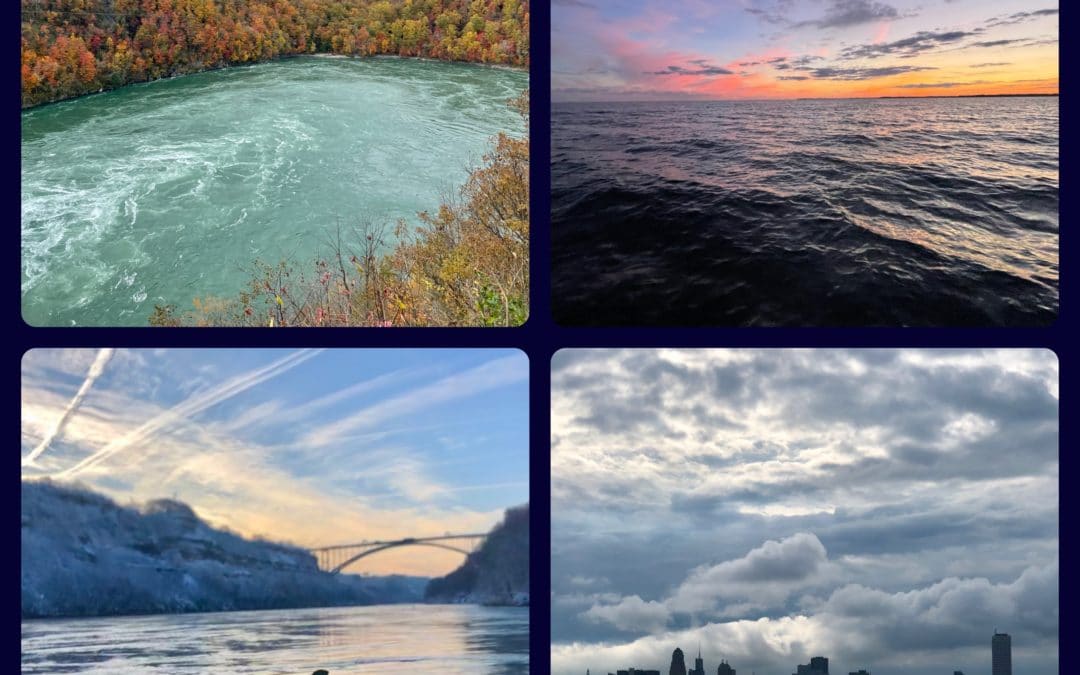

This is going to be a heavy one so make sure you’re settled in with a beverage of some sort. If you’ve read any of my content, you know that I am a pathological ponderer (maybe I’ve been watching a little too much Letterkenny lately). In keeping with this behavior, I’ve been thinking about a way to kluge all of my Observations from the Water into a story about where we live so people from around here can better appreciate the wonders taking place on the other side of their windows.

Before I trot down this trail, I want to highlight a pattern of modern, “civilized,” humans that I think is unfortunate BUT easily remedied – it’s sort of the reason I felt compelled to put this together…well…that and I think it’s a challenging mental exercise. Civilized folks spend a ton of time behind desks, in front of devices, and cooped up inside, resulting in a massive disconnect with their natural environment. [To prevent this from becoming an arduous read, I’m going to pass on defining “natural” and assume that when I use that word, most people have a sense of what I mean. If you want to take a deeper look into what I think this word means, tap this link.] Back to the disconnect – here’s an example – many people look at a weather app to tell them the temperature outside when they can just walk out the door for a couple seconds and feel it. Most folks have gotten to the point that their default setting is to absorb what a device is telling them about what’s going on outside instead of experiencing it with their senses. That’s kinda crazy.

If you’ve fished with me before, the sentiment about how disconnected from our natural environment we’ve become is something you’ve heard me talk about. I spend a lot of time filling the heads of new clients with the wonders of what’s going on above and below the surface of the water. Often, these folks ask me, “How do you know so much about all of this?” I reply that I’ve had some great mentors, I read a lot, and I’m constantly observing/assessing what’s going on around me while on the water. Looking for patterns and problem solving is constant…so is the connection to the environment.

I believe this constant state of observation/taking it all in, is a behavior every captain/guide exhibits. Sometimes, we do this with intent – we’re trying to figure something out. Other times, we’re passively absorbing what’s going on and storing it – reflecting on what we observed much later. Both modes of operation build intuition and a sense of what’s going on that’s difficult to communicate to someone who doesn’t work in this space. I’ve seen the pinnacle of this kind of intuition at play among the Amerindian natives of Guyana – people whom I admire and believe we can learn a lot from in these device driven times.

The observations that follow are by no means all encompassing. My goal is to illustrate how increasingly wonderous and captivating things become when one considers how much is taking place all around us. It’s my hope that such an illustration will cause people to spend more time outside and build their own intuitions – maybe even challenge me on mine – and forge a greater connection to their natural world. Here it goes…

A Little Context

Quick aside before diving in – I live in the Great Lakes Region. We experience 4, distinct seasons here so it’s easy to break down my observations along seasonal lines. However, as you’ll notice, the notion of a clearly defined “season” is fleeting.

For example – I began writing this on a 60-degree day in the middle of December. Yep, went jogging earlier with shorts and a hoodie on, only a handful of days away from the shortest day of the year. It occurred to me that the imagery most strongly associated with each season usually covers only about a month of that season – the month in the center. The other 2 months on the fringes are periods of transition. So do the math – most of the time, the climate is in flux – stability is uncommon.

Why bring this up? Because in keeping with my stated goal of this little essay, I think folks should be less focused on what a human generated calendar tells them and more focused on the patterns they see all around them. Words like “spring,” “summer,” “fall,” and “winter” conjure imagery that tell an incomplete story about all the amazing things that take place on our planet as it revolves around the sun.

The Approach/Methodology

As I began drafting this essay, it occurred to me that a picture would do wonders to show what I will try to describe in words. I’m not an artist – however – if someone who reads this wants to collaborate on creating some imagery to aid in the description that follows, contact me ASAP.

Lacking a visual aid, I needed to come up with some sort of anchor. There were numerous choices – air temperature, water temperature, moon phase, position of the earth in its orbit around the sun, etc. – and all of these would work. However, the amount of sunlight we receive every day is something we can all relate to. So, I decided to use that as the anchor.

Using the amount of daylight as the anchor, what follows is a word picture of what takes place in our environment. Remember, you don’t need to know the exact number of hours or the exact date – fish, insects, mammals, etc. don’t think in numbers – neither did we until we invented them. All you need to do is observe and feel what’s going on around you and you’ll form a picture of what’s going on in the air, on the ground, and underwater.

Finally, after proof reading this numerous times, I realized that the word “optimal” pops up here and there without a definition. Sure, optimal means best possible or most desirable – and maybe you can describe what that means to you in your life but you don’t have a frame of reference of what that means to another organism. So, I want to add a little to that definition with this – optimal is a state where concern for survival or well-being doesn’t dominate the decision pattern. In other words, calories are ample and the act of consuming them is rarely fraught with life threatening encounters. Hopefully that’s helpful. Ok…Pitter patter – let’s get at ‘er.

Spring

According to us humans, spring begins in the northern hemisphere on the vernal equinox (20-21-Mar). This is when the sun is directly over the equator. Discarding that human observation, it’s when the amount of daylight starts to exceed the amount of darkness.

How will you know when that’s taking place? Let’s pull that string…

On the earth’s surface, increased sunlight…

- …causes plants to bloom – so you’ll see flowers and a lot of pollen around. You’ll also have to start mowing your grass (DAMN!!!)

- … “wakes up” hibernating mammals, reptiles, amphibians, and insects – so you’ll start to see/smell/hear skunks, raccoons, groundhogs, snakes, toads, frogs, mosquitoes, butterflies, etc.

- While all this is going on, you’ll feel warmer outside and start wearing less clothes. You’ll also notice that your mood will lighten and you’ll find yourself craving sunlight.

In the air around you, increased sunlight…

- …causes birds to migrate here to breed. Every morning when you wake up, you’ll hear a chorus of birds. You’ll also start seeing birds you haven’t seen in about 6 months. If you live in Buffalo Niagara, here’s a short list of spring arrivals: robins, green egrets, blue herons, crown black night herons, blue birds, hummingbirds, grackles, great egrets, common terns, Caspian terns, cormorants, hooded mergansers, loons, ospreys. The common trend with all these birds is their diet – they eat other animals/insects – and those sources of precious calories have to be out and about to be on the menu. In other words – as it gets warmer, more food becomes available, so lots of birds show up to take advantage, both for their own nourishment as well as their young.

- You’ll see nests for all these birds as well as the nests of those birds that spent their winter here.

- You’ll notice less and less migratory, arctic waterfowl (more on this when we get to winter)

- If you leave your house for work (it’s so crazy I have to include that caveat these days – but all the more reason to write this), you’ll notice your drive will often be foggy. That’s caused by warm air hitting the colder, surface temperatures of Lake Erie and/or Lake Ontario. It’s surreal.

- Pollen will be everywhere. You’ll notice a yellow dust on your vehicle. You’ll notice it flying through the air – cottonwood seeds are the easiest to pick out as they look like little white parachutes.

Underwater: so…if you see a lot of what’s listed above, it’s a good bet the following will also be taking place…

- As the amount of daylight increases, the air, the ground, and the water heat up. Because the Great Lakes and the Niagara River are so deep and because water is dense, it heats up slower than the air and ground. That phenomenon is responsible for the foggy commute mentioned above.

- As the water temperature increases, aquatic insects begin to hatch.

- First are the chironomids (tiny black flies that don’t bite but are a serious pain in the butt as they form huge swarms on windless days). Even if you’re not on the water – you’ll see them form clouds over the roads and near the tops of trees. These bugs are near the base of the food chain – small fish eat them – nowadays, mainly gobies – and they emerge from the sandy/muddy substrate on the bottom of the Great Lakes. So, when the water heats up, the chironomids start emerging – that activity brings in the small bait fish looking for an easy meal – and all those bait fish around bring in large predator fish looking for the same.

- Second are mayflies – but we don’t get a lot of them around here. We do get them, and it induces a feeding pattern like when the chironomids emerge, but mayflies are far more of a factor in western Lake Erie, near Ohio – not my turf.

- Third are caddis – but I’m going to save that for the early summer pattern

- …a lot of sexual activity starts taking place

- Emerald shiners and smelt – 2 of the main forage species for many of the predator fish in the Great Lakes – begin spawning. They move into shallow water and form large spawning schools. This makes them easy targets for every predator out there – above and below the surface. The fact that they spawn when they do is important – sexual activity is calorically taxing and as you’ll see, many of the native predator fish as well as some of the stocked fish spawn in the spring. Having all those emeralds and smelt around ensures the predators can survive the spawn. Go to the river’s edge, anywhere there are docks or a little cove – you’ll see large schools of one or both little fish. After a successful spawn, the newly hatched fry of these fish will remain in the general area, in the cover of weeds, current, and rocks, until they mature enough to migrate to the deeper, colder water of the lakes.

- Steelhead make a spawning run up the regional tributaries. The window is somewhat short, but it is fast and furious. The females make something like a nest on the bottom called a redd. Once formed, they lay their eggs, the males compete for position then fertilize them, and then they all depart – back to the Great Lake from whence they came.

- Muskellunge and northern pike move into shallow, sandy flats to spawn. These fish are area spawners – meaning males will gang up on pregnant females and harass them until they release their eggs. The eggs fall onto the sand, the males fertilize them, and then they head back to deeper water.

- Walleyes are the next to spawn and do the same thing as muskies, just in much larger numbers.

- Smallmouth bass spawn next. They take full advantage of the presence of emerald shiners as well as the goby to pack on as much weight as possible – probably because their spawn is the most taxing of all the regional fish. Males will build nests in gravel, just outside the main current, with plenty of cover around – usually in weeds and rocks. The female will pick a nest, lay her eggs, the male will fertilize them, then the male will remain on the nest until they hatch. He will guard them with his life – fending off any predators – all while living off the fat he built up in the preceding weeks. Once the eggs hatch, he’ll escort the babies (fry) – sometimes in the mouth – to somewhere safe – usually in weeds – where they can hide, feed, and grow.

- Crawfish, another important creature near the base of the food chain, emerge from under rocks to spawn adding another source of calories to menu.

- Carp and freshwater drum spawn last – (there’s overlap with the spawning periods for all of the aforementioned fish but this is the general order). Like muskellunge, pike, and walleyes, carp and freshwater drum are area spawners.

- More daylight and increased water temperature also stimulate zooplankton and phytoplankton reproduction. These microorganisms are the base of the food chain and many of the small bait fish consume them. The Niagara River will concentrate and transfer billions of these microorganisms from Lake Erie into Lake Ontario – forming a plume or a cloud of greenish water. That plume brings in bait. That bait brings in predators – mainly king salmon, coho salmon, lake trout, and brown trout.

Spring Pattern Summary

To try to sum all this up – spring is a period of recovery/renewal. Recovery from a lack of food throughout the winter, or from hibernation – as exhibited by feeding frenzies all around you. Renewal – in the form of mating/breeding/reproduction – as exhibited by…you get the picture. Depending on the rate at which things heat up, you’ll notice all the above in slow progression and in violent spurts but as long as the earth revolves around the sun, it’ll all go down and it’s awesome to behold if you just pay attention. Take advantage of this – because when it starts to get hot outside, your focus will shift to other things…

Summer

According to us humans, summer begins in the northern hemisphere on the summer equinox (20-22-June). This occurs when the North Pole has it’s maximum tilt toward the sun. Discarding that human observation, it’s when the amount of daylight is the longest of the year and it’s the beginning of the hottest weather.

How will you know when that’s taking place? Let’s pull that string…

On the earth’s surface, increased sunlight…

- …brings plants into full bloom – leaves spread out in to take in as much sun as possible.

- … causes most animals to operate in the early morning and late evening…sometimes becoming completely nocturnal. Us mammals tend to get lethargic when we get hot – especially those with a lot of hair. Amphibians will cook in the sun if they spend too much time out of the water, so they exhibit the same behavior as mammals. Reptiles will sun themselves on flat surfaces during the day. Insects will be active throughout the day but like all the aforementioned creatures, most of their activity will take place at night (think about when you get bit by mosquitoes or how many bugs you see flying around streetlights)

- While all this is going on, you’ll find yourself covering your body with less clothes to remain cool and absorb as much sun as possible.

In the air around you:

- All of the birds mentioned in the “Spring” section above, now have kids to take care of. Most of them will be able to fly at this point and will be honing their skills for survival. You’ll notice some rough plumage on many of these birds – those are the young ones. Just like their counterparts that reside on the earth’s surface, birds will be the most active during the early morning and late evening hours – when the temperature is at its lowest with just enough light to be able to see well enough to find food.

- The weather will be “stable” – compared to the other times of year, the probability of large temperature swings and big wave generating winds is the lowest of the year during the summer.

Underwater: so…if you see a lot of this summer activity taking place around you, it’s a good bet the following will also be taking place below the surface…

- Once we get into summer, aquatic insect activity stays mostly underwater (larva/pupae living on the bottom or flowing with the currents) with one notable exception:

- Around here, we get a huge caddis hatch. Locals call them sand flies – I’m not sure why. Maybe it’s their color. Maybe it’s because in their larval form, some of these bugs live in the sand. Whatever – they are caddis – and they hatch from the water like a lake effect snowstorm. Once hatched from an egg, the larval form of these bugs builds a protective shell out of the materials that surround it – sand, weeds, leaves, etc. They stay in this form, clinging to rocks and aquatic plants, eating microorganisms, breathing through gills, for about a year. Once the water temperature heats up into the upper 50s low 60s, they shed that shell, blow an air bubble, ride it to the surface, spread their new wings, and fly away into the trees to rest. Shortly thereafter, usually the next morning or evening, they leave the trees, and mate over the water. The male dies and falls to the surface (fish food). The female forms a small, green egg and she deposits it by dapping the surface of the water (you’ll see them, seemingly bouncing off the surface) …then she dies too.

- …a spreading out or migration takes place

- Emerald shiners, smelt, and the invasive alewife disperse from the huge schools you may have noticed in the spring and move to deeper water where it’s cooler. In other words, you won’t see them near docks anymore.

- As in the spring, most of predator fish follow the schools of bait – so king salmon, lake trout, steelhead, brown trout, and walleyes move to deeper, colder water. Currents throughout the lakes constantly move water of varying temperatures and many creatures move with it – following their “optimal” batch of water. This causes fish to spread out and to come together – if you can find the optimal zones of temperature, you’ll find a lot of life going on.

- Muskellunge and northern pike establish themselves in ambush points and hunker down during the daylight hours. Like all animals, these fish don’t function well when it’s hot so they conserve energy when the water’s warmest and only hunt when the kill will have a large return in calories – a fast strike at a large forage fish during low light hours when the prey is most vulnerable is the preferred tactic.

- Smallmouth bass go on a feeding frenzy after they recover from their spawn. Unlike the predator fish that follow schools of bait, bass don’t travel very far from where they spawn – they don’t have to. Gobies blanket the bottom in most places AND crawfish are prevalent at this point. The bass that live in the great lakes move to deeper water after they spawn – but not super deep. They go to reefs and shoals where they can pick away at gobies and crawfish all day while remaining cool. The bass that live in the river have the current to help keep them oxygenated but they still move a little deeper into cooler water. Just like in the lakes, they occupy areas with plenty of rocks where they have ready access to crawfish and gobies.

- Carp and freshwater drum do a little bit of everything. Some will go deep. Some will stay shallow. Others will cruise around. It never ceases to amaze me where one can find these 2 fish.

Summer Pattern Summary

If you think about the summer pattern of life – every morning and every evening is condensed version of what happens all spring (minus the mating part). All the living things in your environment – especially those you can see, hear, and smell – are like you in that it’s suboptimal for them to operate when it’s hot. This is why every morning and every evening you’ll notice a lot of activity going on around you – everything is trying to capitalize on optimal conditions at the same time. Although it’ll be tough to see, just know that the same is going on underwater. Sure, fish will feed throughout the day when the opportunity presents itself, particularly bass, but like us, they tend to sulk until the conditions around them are optimal.

Autumn

Since I started this list of observations with the “spring” season, you likely noticed that a steady increase in daylight was the catalyst for all the activity. For the fall and winter, a steady decrease in daylight will be the cause. In the Northern Hemisphere the autumnal equinox falls on September 20-22, as the sun crosses the equator going south. In other words, daylight hours are starting to wane and everything around you starts getting the sense that it’s “last call” or the party is coming to an end.

How will you know when that’s taking place? Let’s pull that string…

On the earth’s surface, decreased sunlight…

- …causes plants wither. Some will die. The leaves on others will change color and fall to the ground creating a fertilizer for the following spring. In other words, you won’t have to mow your lawn much anymore…but you’ll have plenty of dead stuff to clean up.

- …all of the animals that hibernate for the winter will start getting frantic and feeding aggressively in order to build up enough fat to live off of over the winter months. As the days grow shorter, you’ll see less and less bugs, reptiles, and amphibians around as they’ve begun burrowing into the ground. Same goes for some of the mammals such as ground hogs, skunks, and raccoons.

- Fall is mating season for many of the large mammals in the Buffalo Niagara region…really, that means whitetail deer. I doubt you’ll see any of that activity taking place, but you’ll likely see male deer with antlers.

- While all this is going on, you’ll feel cooler when outside and start wearing more and more clothes. Apple and pumpkin picking will become a thing as well PSLs. You’ll also notice that your mood will start to get frantic – kids going back to school/busses on the road, football games, tight schedules, fiscal year closeouts, etc. Daylight savings time kicks in during this period adding to the stress of trying to cram activities into a steadily decreasing number of daylight hours.

In the air around you, decreased sunlight…

- …causes some birds to migrate south. All those birds that made the journey up here in the spring will return from whence they came in the autumn – young of the year in tow. They leave because their sources of food are becoming increasingly scarce (remember – bugs are few and far between, plants are dying, amphibians and reptiles are burrowing) and most aren’t adapted for the cold.

- …wind will become more prevalent. I’m not talking about the little breeze that you long for on hot summer days. I’m talking about gale inducing, huge wave generating, and often damaging forces of nature.

- …little white flakes will make an appearance at some point, followed by a chorus of, “I’m not ready for this,” sentiments from the populace.

Underwater: so…if you see a lot of what’s listed above, it’s a good bet the following will also be taking place below…

- As the amount of daylight decreases, the air, the ground, and the water get colder. Because the Great Lakes and the Niagara River are so deep and because water is denser than the air and ground, it cools down slower/retains heat longer. On particularly brisk mornings early in the season, you’ll likely see steam coming off the water.

- As the water temperature decreases, aquatic insects become dormant, or move very little

- …a lot of sexual activity starts taking place

- King salmon are the first to get frisky. Charged up with sex hormones, they return to the rivers where they were born. Although there is some debate in the scientific community about how they find their way back, there seems to be consensus on their use of magnetic fields and scent. I’ve read a couple papers that claim king salmon can “smell” a drop of their home water in 250 gallons of sea water. While they stage to make the run up their home river, their bodies change. Their reproductive system primes (sperm sacs swell in males, eggs mature in females, and sex hormones abound), their digestive system collapses, and the males grow toothed kype jaws. Once in their home river, like the steelhead spawning activity mentioned in the spring section, the female salmon make redds on gravelly bottom, lay eggs, and the males fertilize them. Unlike the steelhead, king salmon die after spawning – transferring an untold number of calories from the lakes to the tributaries where they’ll be absorbed/consumed by plants, insects, and scavenging animals.

- Lake trout are the next fish to make a spawning run. Throughout the Great Lakes Region, lake trout migrate to shallow shoals (and the Lower Niagara River) once the water temperatures drop into the 50s. Their spawning activity mirrors that of king salmon and steelhead. Like steelhead, they don’t die after the spawn – they return to the depths of the large body of water from whence they came.

- Brown trout are the next fish to make a spawning run. Their behavior mirrors the lake trout this time of year.

- Steelhead are next to make a spawning run up the regional tributaries. If you recall from the “Spring” section above, steelhead make a spawning run in the spring too. Well, some of the fish decide to make a run in the fall as well. These fall running fish start arriving as early as late September and their peak population will be in place roughly before the new year. There is no consensus regarding why there are 2 runs of fish, however, those fish that make the run in the fall will have plenty of food to carry them over til their spring spawn. Salmon eggs, lake trout eggs, and bait fish like juvenile smelt and emerald shiners form a robust menu of forage options throughout the winter.

- A feeding frenzy takes place. Musky, walleyes, smallmouth bass, and freshwater drum feed aggressively in the fall. Unlike the trout and salmon mentioned above, these fish “prefer” water temperatures between 40 and 60 degrees (roughly). Quick side note – I’m not trying to anthropomorphize here but I want folks to understand that all creatures, including us, have an optimal temperature. “Optimal,” in this context, means that maintaining body weight or even better, increasing body weight, isn’t taxing. So, as water temperatures start to decrease, the aforementioned fish start to get frantic. Think about your reaction to seeing the first snowflakes of the year – “I’m not ready for this.” Well, the fish version of that would be, “I need to get ready for this ASAP!” Eating big meals as often as possible becomes the pattern – often these fish will be bloated with food. This feast will build enough fat for the fish to live off of when the water drops below the “suboptimal” range in the winter.

Autumn Pattern Summary

To try to sum all this up –autumn is a period of preparation and a little bit of renewal. Praparation for the winter via feasting/transfer of energy – as exhibited by the feeding frenzies around you and all of the dead things on the ground. Renewal – in the form of mating/breeding/reproduction. Yeah, this sounds a lot like spring, and it is in many ways. However, there’s something frantic about autumn – like fear is a huge motivator. In the spring, the days are getting longer, it’s getting warmer, growth is happening all around you – hope “springs” eternal. In the fall, the opposite of all of that is the case. Shorter days and cooler temperatures create a sense of unease…like something ominous is on the way…like you’re being robbed of time and comfort. Well – winter is approaching so…

Winter

According to us humans, winter begins in the northern hemisphere on the winter equinox (20-22-December). This occurs when the North Pole has it’s minimum tilt toward the sun. Discarding that human observation, it’s when the amount of daylight is the shortest of the year and it’s the time of the coldest weather.

How will you know when that’s taking place? Let’s pull that string…

On the earth’s surface, minimal sunlight…

- …brings about the death of the annual plants and nearly halts the growth of the perennials (like trees). If the ground isn’t covered by snow, it’ll likely be brown. Since little to nothing will be hanging from the trees, you’ll be able to see far deeper into the woods than you can during the rest of the year. If you float the lower Niagara, you’ll see details in the rock strata that you can’t see when everything is full of life.

- …will cause many land-dwelling animals to hibernate. Most of the animals you’re used to seeing throughout the year won’t be around anymore. Sure, you may see some deer, squirrels, rabbits, mink, and the occasional turkey…but not much else. Often times, you’ll see these animals in the middle of the day, taking advantage of the short windows of “warmth” offered by the midday sun.

- While all this is going on, you’ll find yourself covering your body with multiple layers of clothing. You may find yourself spending a ton of time indoors, inducing numerous bouts of shack nasties, or worse – depression.

In the air around you, you’ll notice…

- …some of the same birds you’ve seen throughout the year like mallards, Canadian geese, chickadees, starlings, blue jays, cardinals, redtail hawks, and peregrine falcons. Other than the raptors, these birds remain here because they are well adapted to eat seeds – and many of the plants in this region dispersed PLENTY of these precious calorie packs back in autumn. Now that there aren’t any leaves on the trees, you’ll likely notice many raptors around as they stand out when perched on the branches or fence posts. They have a new set of challenges – lack of foliage makes it easier to pick out targets…until the white stuff covers the ground, and their prey can tunnel around in it.

- The weather will be somewhat stable for extended periods of time. Although temperatures will hover around freezing and the sun will rarely make an appearance through a seemingly permanent shroud of clouds, wind and huge temperature swings will be less of a factor compared to the spring and fall.

- Background noise will dwindle to a low hum. Think about it – you can easily hear a breeze in the summer – you can thank foliage for that. In the winter, there’s no foliage around so the breeze blows through leafless branches at a whisper. Like I mentioned above, there aren’t many birds around in the winter so other than the occasional jay, chickadee, or cardinal, you could go days without hearing a bird. Also, if there’s snow on the ground, it serves as an incredible noise absorber.

Underwater: so…if you see a lot of this winter activity taking place around you, it’s a good bet the following will also be taking place below the surface…

- Although it takes far longer for the water to cool than it does for the air and ground, after dozens of short days and cold air temperatures, the water temperatures drop to points hovering around freezing. In most years, over 80% of the surface of Lake Erie will freeze (insert link here).

- The Niagara River will seem to be flowing by…slowly. By mid winter, surface temperatures sometimes hover at or slightly below 32 degrees so it’s closer to solid than liquid. Walk to the bank, dip a stick into the water, pull it out and watch it drip off the end – it’ll almost look like clear syrup.

- Aquatic insect activity grinds to a near halt. On days when the sky is clear and the breeze is down, tiny chironomids and stoneflies will hatch from the gravel and rocks near the warmer water on sunlit banks. Otherwise, most aquatic insects are moving around slowly in those frigid temperatures.

- Thousands of artic sea ducks will arrive and remain through the spring. These birds journey south from places as far north as the arctic circle to stay in our region as it provides a huge source of food and open water throughout the winter. I’m not sure what’s common knowledge, but I think that when most people think of ducks around here, they picture a mallard…a bird that spends all of it’s time on the surface of the water or on land. The sea ducks that come here…don’t. Many of the winter migrators dive to depths over 50’ (long-tailed ducks can dive to 200’), feed on baitfish and shellfish, and rarely spend time on land (around here that is).

- Thousands of arctic gulls will arrive and remain through the spring. Just like the sea ducks, these birds vacation here in the relative warmth of the Buffalo Niagara Region from places as far as Greenway, Alaska, and Iceland. Again, I’m not sure what’s common knowledge, but I think that when most people think about gulls, they picture the ringbill gull they saw in a parking lot near a fast-food restaurant. Although very similar in appearance, these arctic gulls, aren’t what you saw in the parking lot. They are highly effective fish hunters that can pick out a baitfish the size of your pinky, in fast current, while hovering 50’ over the water. They’ll get a thick as snow on the lower Niagara – especially when the wind is up and it’s tough flying for them over the lakes.

- …a spreading out or migration takes place

- Emerald shiners, smelt, and the invasive alewife disperse throughout the lakes in pursuit of warmer water. The sunniest, calmest of days, will warm the shallow water near the banks just enough to attract large schools of bait for a couple hours.

- As in the summer, most of predator fish follow the schools of bait – so king salmon, lake trout, steelhead, brown trout, smallmouth bass, and walleyes move to warmer water as well. However, even though these fish will find warmer batches of water amidst all of that near-frozen stuff, it’ll still be cold. As with all cold-blooded creatures, when it gets cold, fish slow down and conserve energy. In turn, their caloric requirements are a small fraction of what they need throughout the rest of the year. Now is the time they live off the fat they packed on back in the fall, supplemented by an easy meal – one that doesn’t take much effort to consume.

- The steelhead that ran in the fall and some of the lake trout that spawned in the fall, will remain in the Niagara River throughout the winter. The cold water and fast current frequently dislodge aquatic insects, gobies, small schools of bait, and eggs from the bottom/current breaks, sending it all downstream. This conveyor belt of food serves up enough calories to keep these fish active and strong throughout the winter. As with the animals on land, the peak time of day for this activity seems to be around midday.

Wintern Pattern Summary

When considering the winter pattern of life, one thing becomes obvious – it’s the time of year when it’s ridiculously easy to recognize the importance of the sun. Afterall, it’s dark way more than it isn’t in the winter. Even when it’s light out, conditions are taxing for just about everything. Risk calculation is rife – every effort must yield a net benefit in calories when dealing with razor thin margins. Opportunities to eat are short and intermittent. Starvation looms. Still, as trying as this time of year can be for all living organisms, there is a beauty unique to the winter. The quiet, the stillness, the kaleidoscopic reflection of light shining off ice on a sunny day. Maybe that’s why things seem to rejoice on a sunny, winter day.

Conclusion

Thank you for reading! I know – that was over 6K words – but I hope it was easy to read and that you learned something about what’s going on outside your window. I also hope that you spend more time out there – observing some of what was discussed, making observations of your own, challenging mine, and talking to others about it all. I use the word “observing” (noticing or perceiving something and registering it as being significant) for a reason. Observation doesn’t merely occur via your eyes (just ask a blind person) – your sense of smell, touch, and sound are equally important toward forming a picture about what’s going on around you. The more you employ all your senses in your native environment, the deeper your connection to it all will become. It’s a wonderous and complex place that will captivate you far more than any illuminated rectangle – all you need to do is walk out that door.

Stay healthy my friends, mentally and physically –

Ryan

Very well written and informative. I’ve been an outdoor enthusiast and fisherman of our local waterways for many decades. I woke up early this morning thinking about and hungry for more knowledge on the subject. This was exactly what I was looking for! 👏 Bravo Ryan, Great job summing up such an intimidatingly large subject in only 6k words!

Thank you very much for taking the time to read this essay. It was a labor of love. I’m glad you enjoyed it.